My Research

Recent Publications

Attaway, S. E., Penwell, T. E., Weissman, R. S., Pruscino, I., Hogan, A., & Martin-Wagar, C. A. (2025). Who is included in studies of night eating syndrome? A scoping review of reported participant characteristics. Eating Behaviors, 58, 102017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2025.102017

Description

Our group conducted a review of the existing literature to explore which participant characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race, etc.) are commonly reported in studies on night eating syndrome and how frequently studies use weight or weight class as part of their inclusion criteria. We found that most studies do not report any characteristics or report very few characteristics on participants with night eating syndrome. Several studies used weight, body mass index, or weight class as part of the criteria for who was included in the study. The limited reporting on participant characteristics makes it difficult to understand who is most at risk for developing night eating syndrome.

Penwell, T. E., Bedard, S. P., Erye, R., & Levinson, C. A. (2024). Barriers to eating disorder treatment access in the United States: Estimates of perceived inequities among reported treatment seekers. Psychiatric Services. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.20230193

Description

In a collaboration between the Eating Anxiety Treatment Lab and Project HEAL, we explored why individuals with eating disorders have difficulty accessing specialized eating disorder treatment. Financial barriers (like insurance denial or being unable to afford treatment) were the most common barriers for individuals trying to get eating disorder treatment. Also, individuals from underrepresented backgrounds (like racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQIA+ individuals, individuals with a disability) were more likely to report barriers than historically represented individuals (like White/Caucasian individuals, heterosexual and cisgender individuals, and individuals without a disability).

Highlights

-

Statistics from this publication have been used to support legislative changes in Colorado (SB23-176: Protections for People with an Eating Disorder) and Kentucky to improve access to eating disorder treatment.

-

Find an infographic and social media toolkit here!

Penwell, T. E., Smith, M., Ortiz, S. N., Brooks, G., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2024). Traditional versus virtual partial hospital programme for eating disorders: Feasibility and preliminary comparison of effects. European eating disorders review: the journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 32(2), 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.3031

Description

In collaboration with The Renfrew Center, we explored whether a partial hospital program (which is when people go to treatment for 6-8 hours a day, 5 days a week) had similar treatment outcomes from admission to discharge when done virtually (over zoom) compared to in-person. Both programs treated patients with the Renfrew Unified Treatment for Eating Disorders and Comorbidity. Individuals in both treatment types (virtual and in-person) saw similar reductions in eating disorder symptoms and behaviors (like self-induced vomiting, exercise, and laxative use), depression symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. Individuals who received treatment in-person had significantly more weight gain by end of treatment than those received virtual treatment. Overall, the study supports that partial hospital programs can be completed virtually with similar treatment outcomes as in-person treatment, but individuals who need to gain weight may benefit more from in-person services.

Highlights

-

Graphs showing the treatment outcomes can be found on The Renfrew Center's Research & Outcomes page.

Christian, C. B.**, Nicholas, J. K.**, Penwell, T. E., & Levinson, C. A. (2023). Profiles of experienced and internalized weight-based stigma in college students across the weight spectrum: Associations with eating disorder, depression, and anxiety symptoms. Eating Behaviors, 50, 101772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2023.101772

**both authors are first author

Description

Weight stigma is a very common and accepted form of stigma that includes negative attitudes, discrimination, rejection, and prejudice against individuals in larger bodies. Our study explored how types of weight stigma (like policy level or relationship related), internalized weight stigma (when people apply negative attitudes related to weight to themselves), and weight status relate to each other and to mental health symptoms. Using a large (1001 individuals), undergraduate student sample, we found five profiles (that is, groups with similar responses) of weight stigma, internalized weight stigma, and weight status. The profile with individuals who reported high weight stigma, high internalized weight stigma, and high weight status reported the highest levels of eating disorder symptoms, depression symptoms, and social anxiety symptoms. Overall, the study supports that weight stigma and internalized weight stigma is related to negative mental health symptoms.

Highlights

-

This study was recently included in a large review on weight stigma and eating disorder symptoms.

Recent Presentations

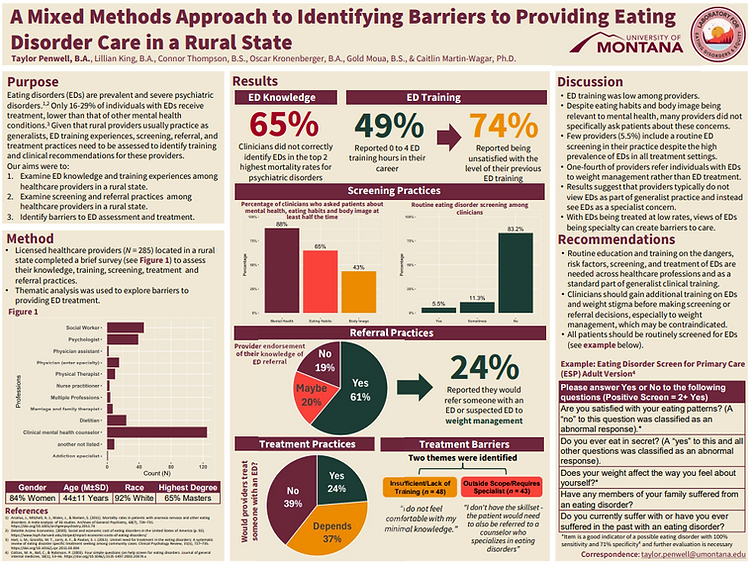

Penwell, T. E., King, L., Thompson, C., Kronenberger, O., Moua, G., & Martin-Wagar, C. (2024, August 10). A Mixed Methods Approach to Identifying Barriers to Providing Eating Disorder Care in a Rural State. [Poster]. American Psychological Association, Seattle, WA.

Description

To address treatment access barriers for rural individuals with eating disorders, it is important to explore rural provider's knowledge and training on eating disorders along with their eating disorder screening, referral, and treatment practices. In our study, we asked providers in a rural state to complete a brief survey on eating disorder knowledge, training, and practices. Majority of respondents were Clinical Mental Health Counselors. Most (65%) of providers did not identify eating disorders in the top two for highest mortality rates of all psychiatric disorders (opioid use disorder is number 1 and eating disorders are number 2). Almost half of providers reported 0-4 training hours on eating disorders and majority stated they were dissatisfied with their previous eating disorder training. Most providers screen for mental health concerns, but do not see eating habits and body image as part of mental health screenings. Few providers (5%) are routinely screening for eating disorders in their practice. Over half of providers reported that they know where to refer someone with an eating disorder; however, 24% reported they would refer someone with an eating disorder to weight management treatment. Finally, only 24% reported treating individuals with eating disorders and identified that insufficient or lack of eating disorder training and seeing eating disorders as outside of their scope of practice or as a specialty concern were the two most common barriers to treating eating disorders. Overall, eating disorder training, knowledge, screening, and treatment practices are low among rural providers. We recommend that training on eating disorders and weight stigma are needed across healthcare professions and eating disorders need to be seen as part of generalize practice to increase access to care.

Penwell, T. E., Crumby, E., & Levinson, C. A. (2023, November 19). Characteristics of Individuals Recently Discharged from Intensive Eating Disorder Treatment and Subsequent Relapse. [Eating Disorder & Eating Behavior Special Interest Group Poster]. 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Cognitive and Behavioral Therapy, Seattle, WA.

Description

People with eating disorders have high rates of relapse (that is, symptoms come back and/or they return to treatment) after finishing intensive treatment (like inpatient hospitalization). We wanted to look at what characteristics (like demographics or symptoms) may relate to relapse 1 month after treatment and 6 months after treatment. At 1 month after treatment, 16.4% of people in our study had relapsed, but we did not find any significant predictors of relapse at 1 month after treatment. At 6 months after treatment, 47.2% of the people in our study had relapsed. We found that people who relapsed at 6 months after treatment reported significantly higher eating disorder symptoms, depression symptoms, and eating disorder symptom impairment at discharge from treatment than those who did not relapse 6 months after treatment. Overall, our study supports that including treatments of depression in eating disorder relapse prevention treatments could be helpful. More research is needed to find what may be related to relapse 1 month after treatment.

Need access to one of my publications?

Use the contact form to ask for a copy!